Identifying and Preventing Escalating Behaviors in Children

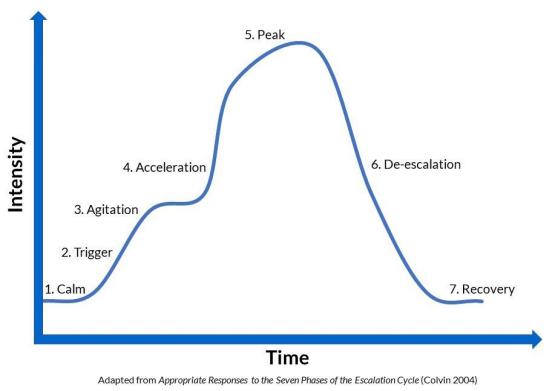

Children often experience ‘big emotions,’ getting caught up in joy, sadness, anger, and fear in strong, often intense, ways. When overwhelmed by these feelings, our children ‘act out,’ and escalate emotionally and behaviorally. Although we should expect our children to act out at times as they learn to regulate their emotions and problem-solve, sometimes these escalations can lead to problems academically, socially, and personally. Every child experiences and expresses their emotions differently but the escalation pathway often follows similar patterns and is described in the Escalation Cycle, as shown below.

It is important for caregivers and educators to better understand this cycle, as depending on the stage our child is in, different techniques may be helpful. This cycle, as proposed originally by Colvin (2004), highlights that acting out does not emerge from nowhere, there is a process and a lifespan of the escalation. He highlights seven unique stages, as shown below. This blog post will center around the first three stages of the escalation process: 1)Calm, 2) Trigger, 3) Agitation. It will also describe effective ways of identifying potential triggers and preventing escalations at home and school. An upcoming second post will center around what to do when a child has already become escalated.

Stage 1: The Calm stage

The Calm stage is the first stage of the acting out cycle, when your child is at their emotional ‘baseline,’ and where they are best able to able to complete tasks, engage in social, cooperative behavior, and productively problem solve. Parents and teachers who are able to maintain strong, supportive relationships with their child are more likely to help their child stay in the calm phase more frequently and effectively. This calm stage can also be reinforced through ensuring the child has clear boundaries and expectations, positive, constructive feedback, predictable routines, and helping the child understand how to request help or assistance.

Stage 2: The Trigger Phase

When our children become escalated, it can sometimes feel like it came out of the blue. However, escalation almost always begins with a Trigger. Triggers almost always arise from a concern, problem, or unmet need a child is facing in that moment. That will then lead the child to experience strong emotions, such as sadness, fear, or anger, and escalated behavior that may be an attempt to solve the issue (such as refusing to do work, shouting, crying, or hiding).

An important reminder about triggers is that a trigger is not just a result of the external event, but also influenced by internal factors as well, such as how the child interprets the event. For example, for some children, a change in schedule may be a pleasant surprise, but for others, it may cause them to become confused or frustrated. Additionally, other factors, such as hunger, thirst, tiredness, sickness can also predispose children to responding strongly to triggers more negatively (Just like with us adults!). Lastly, if the child is experiencing stress or conflict at home, they may be more likely to respond more strongly to issues that arise at school, and the same is true the other way around.

Prevention is often the best way to avoid further escalation with the child, and because of that, it is the crucial that adult caregivers and teachers get a thorough understanding of their children’s triggers, and how these triggers make them feel and react. Ways you can help learn about your child’s own triggers include:

• Talking with your child after the escalation to understand what happened from their perspective, and if they could identify what triggered them.

• Journaling or tracking your child’s escalations, to see if you pick up any themes or patterns.

• Asking others who know your child, such as teachers, parents, or therapists, to compare notes.

• In some cases, taking your child to be evaluated by a behavioral professional (Psychologist, Therapist, Psychiatrist), may be warranted if triggers cannot be easily identified.

Once you better understand your child’s triggers, you can develop ways to prevent and minimize their effects on your child. If a certain trigger is present for your child, you know that they may need extra attention and support during this time. You may also be able to redirect your child away from the trigger by focusing their attention on something else. However, some triggers may not always be able to be removed. In this case, you may wish to work with your child to develop plans that they can work on together with you for when they are next exposed, which may encourage the child to practice both problem-solving skills as well as emotion regulation and self-soothing techniques. You may also wish to work with an educational or mental-health professional to develop a plan for how to cope with certain triggers for when they emerge.

Stage 3: The Agitation Stage

Although identification and prevention of triggers are key, caregivers and educators cannot control every aspect of the child’s environment, and children are not able to always perfectly cope with and respond to triggers (And neither are many adults!). If the trigger is unable to be addressed, then the child may begin displaying agitation, which can be displayed both verbally and nonverbally and indicate that the child is on the path of escalating and if intervention is not taken, then their emotional and behavioral responses will quickly increase. This may be the last stage where the child may be able to be redirected before the escalation begins to progress in earnest. some common signs of agitation include:

• Fidgeting

• Tapping hands or feet

• Avoiding eye contact or looking around the room

• Engaging in off-task behavior

• Starting and Stopping work

• Isolating or avoiding others

• Vocal sounds of distress

• Tense, rigid posture

Agitation can build up in a student for a prolonged period of time after the initial trigger. A triggering event in the morning may simmer within the child for hours as their agitation grows, and may not be released into a full blown explosion until that afternoon. The sooner the agitation is addressed, the easier it will be to restore your child to the calm stage. The main way of restoring calm is through offering supportive, empathic help to your child. If caught early, this can be as simple as spending some time giving them positive attention or giving them a quick break from whatever tasks they were doing. You may also want to help them by offering pleasurable or relaxing activities for them to engage in.

In older children, it may be helpful to validate your child’s agitation and engage them in a supportive conversation about how you can help. Some useful tips are below:

• Keep eye contact

• Offer validation and praise

• Be mindful of proximity: Do they want you close or do they want some space?

• Offer your child choices and options

• Offer to help them relax through relaxation techniques or movement activities

• If they need to be doing something, try offering ‘start’ requests instead of ‘stop’ (“Can you start doing _____?” vs. “Stop doing _____”)

When agitated, it is important to not:

• Yell, Raise your voice

• Nag or preach

• Use sarcasm

• Make assumptions you know exactly what is going on

• Get caught up in an argument or insist you are right

• Use judgmental or blaming language.

If the child continues to remain agitated, then they may proceed to the 4th stage, Acceleration. At this point, the escalation process will be significantly more difficult to interrupt or redirect. In the next article, we will go over the remaining stages of the escalation cycle, what they are, and what to do if this stage is reached.

References:

Colvin, G. (2004). Managing the cycle of acting-out behavior in the classroom.